Laminitis: Why Your Horse Standing Camped Under Could Indicate pain

Does your horse stand with his front feet out in front of his shoulders and his hind legs unusually under his body – this being commonly known as “camped under”?

The following are all symptoms of your horse developing laminitis:

- Your horse is walking stiffly.

- Your horse doesn’t want to walk at all.

- He keeps moving from foot to foot and looks uncomfortable when standing normally.

- His hooves are warmer than usual – usually the front warmer than the hind hooves.

- Can you feel the pulse at the back of your horse’s pastern pulsing stronger than the other hooves?

- Is he standing “camped under” with his front legs stretched out further than usual and his hind legs further under his body than usual?

Laminitis is a serious condition that affects the feet of horses. It occurs when the sensitive laminae that connect the horse’s hoof wall to its bones become inflamed and damaged, leading to pain and instability in the horse’s feet. Laminitis can have a number of causes, including overfeeding, obesity, founder, metabolic imbalances, and certain diseases and infections.

Laminitis is a complex condition that can have a significant impact on a horse’s health and mobility. In severe cases, it can lead to the separation of the hoof wall from the underlying bones, which can cause the horse’s foot to become deformed and unable to support the weight of the horse. Early detection and treatment of laminitis is critical to minimizing the impact of the condition and ensuring the best possible outcome for the horse. Horse owners and riders should be vigilant for the signs and symptoms of laminitis and seek veterinary care if they suspect that their horse may be experiencing this condition.

Laminitis is a potentially devastating disease that can end your horse’s riding career and possibly lead to euthanasia. We had a desperate case of it ourselves from a mare retaining a placenta after aborting her foal from being bitten by a snake.

Laminitis is not an easy disease to treat and farriers and vets have been frustrated with the best way to treat it. Thanks to advances in molecular biology researchers are getting some answers.

This article is going to discuss these advancements, how to diagnose laminitis, what it does to your horse’s hoof, and how to treat it.

The anatomy of the laminae

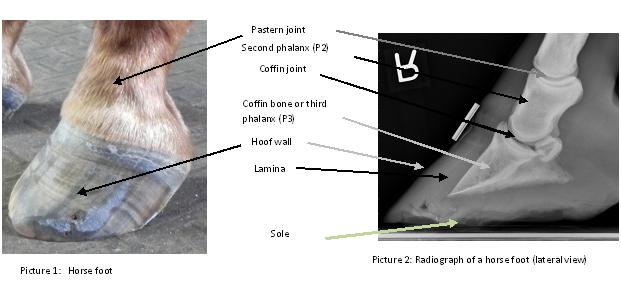

To understand how laminitis affects your horse it is a good idea to have a general idea of how the hoof is configured. hoof anatomy

Delicate, leaflike structures called the laminae secure the hoof wall to the coffin bone. The coffin bone is also known as the third phalanx, distal phalanx or P3. The inner laminae (also called the dermal or sensitive laminae) are extensions of connective tissue adhered tightly to the coffin bone.

The Laminae mesh like interlocking fingers with the outer (also known as the epidermal or insensitive laminae) which line the inside of the hoof wall.

The inner laminae are rich in nerves and blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients to the outer laminae. A thin basement membrane, interwoven with the tissue of the inner laminae, is attached to the epithelial cells on the surface of the outer laminae.

There are usually about 600 primary laminae in each foot and each one is feathered with tiny extensions called secondary laminae. That feathering increases the total surface area and allows the two sides to grip like Velcro.

The bond between the basement membrane and the epithelial cells is so strong that it can hold the horse’s entire weight, catching the load carried down through the leg to the coffin bone and transferring it out to the hoof wall.

This bond is also dynamic, as the hoof wall grows, epithelial cells periodically release their grip and migrate down, replaced by new cells generated in the coronary band while maintaining enough hold to support the horse’s weight.

How does laminitis develop?

When Laminitis develops this well-orchestrated system breaks down. The laminae lose their grip on each other and the coffin bone begins to pull away from the hoof wall.

This separation usually starts at the toe. Then the bone, which is normally positioned parallel to the front of the hoof wall rotates vertically. The pull from the deep digital flexor (DDF) tendon, which runs down the back of the horse’s leg and anchors onto the back of the coffin bone, encourages this rotation.

Even a small degree of rotation is excruciatingly painful. The tip of the bone presses down, crushing soft tissues below it and sometimes even pushing through the sole just in front of the frog.

In severe cases, the laminae may give away all through the foot and the entire coffin bone sinks into the hoof capsule. Often both sinking and rotation occur. In these cases, the horse’s outlook is very poor.

Laminitis most often strikes adult horses and all four feet can be affected. It is more usual for both front feet to be affected because the front feet take 60% of the horse’s weight.

According to studies only colic leads to more veterinary care and ultimately to having to be euthanized. Luckily only 5% of cases become this extreme but this is much higher in severe cases.

Why Laminitis develops

Certain conditions greatly increase your horse’s risk of getting laminitis:

- Horses getting too many carbohydrates. If a horse goes onto very fertile spring grass after being on dry hay all year or is fed too much grain.

- Metabolic problems. Some horses have metabolic disorders when they are overweight and those with Cushing’s disease are put at high risk.

- A severe gastrointestinal disease that causes severe diarrhea or colic that compromises the intestine.

- Pneumonia and infection in your horse’s lungs and the pleura (membranes covering the lungs)

- Acute uterine infection from a retained placenta after foaling (which is what happened in our case).

- Toxins that your horse ingests.

- Lameness in other legs causes stress on an alternate leg.

Many of these conditions have a common thread – they provoke a whole-body inflammatory response similar to human sepsis. In humans when in sepsis the whole body overreacts to an infection setting off a cascading series of events that lead to overwhelming inflammation which can lead to organ failure. In horses, this leads to laminitis and the failure of the laminae.

Usually within 24 to 72 hours after the triggering event can show the first signs of laminitis but the inflammation starts immediately before the symptoms start to show. The horse still looks sound but the damage has already started, quick action is vital.

Act quickly

As soon as your horse starts showing signs of laminitis call your vet. Early treatment of whatever has caused your horse to develop laminitis can help prevent extreme cases. Early treatment can stop the chain of events that cause the coffin bone to sink or rotate.

Look out for the following symptoms:

- A stronger than usual digital pulse at the back of your horse’s pastern.

- Obvious heat in your horse’s hoof, compare this to the other hooves.

- Any form of lameness ranging from walking stiffly to a hoping gate to your horse not wanting to walk at all.

- Standing awkwardly. If your horse is standing with his front feet stretched out in front of him and has his back legs further under his body than usual. This is called “camped out”.

Acting quickly when any of these symptoms are noticed is very important.

Your vet will do a few tests on your horse while diagnosing laminitis. He may nerve block both front feet to see if the back feet are also involved and will take X-rays. Horses who are affected in both front feet tend to have their coffin bones sink rather than rotate. X-rays will show if the coffin bone is displaced.

Taking X-rays is essential to serve as a baseline for noticing changes in the treatment ahead. These X-rays can often not show the extent of the infection in the laminae but are a useful tool in keeping track of the rotation of the coffin bone.

Treatment

Treatment is focused on fighting the acute attack of the laminae and focuses on stopping the cycle of the inflammation and protecting the feet as much as possible.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are essential drugs in fighting laminitis. These drugs seem to block multiple inflammatory pathways.

- Standing your horse in iced water. The cold slows the actions of the destructive enzymes and can decrease inflammation.

- Analgesic drugs can also interrupt the cycle of inflammation and help the pain.

- Drugs that increase the blood flow to the feet are thought to help.

Protect your horses feet

The goal is to take as much strain as possible off the laminae.

- Remove your horse’s shoes which will put his weight on the hoof wall.

- Tape Styrofoam pads or some kind of commercial support that protects the entire sole of your horse’s hoof.

- Limit movement, and keep your horse in its stable. With the laminae hanging on with threads movement must be restricted.

- Put deep bedding in his stable to encourage him to lie down as much as possible.

If X-rays show coffin bone rotation, some horses respond by raising the horse’s heels to lessen the pull of the DDF tendon on the coffin bone. This is done with pads or putting on specialized shoes.

A hoof that is rapidly deteriorating may stabilize in a cast.

Watch closely

The first two weeks are vital to your horse’s recovery. Call your vet back if:

- Heat and the digital pulse getting stronger.

- If your horse seems to relapse and becomes more uncomfortable. Do not walk your horse around, watch him in his stable, and if he is looking more in pain then call your vet.

- You see cracking on the coronary band or a bulge on his sole. These indicate severe sudden changes inside the foot, the coffin bone is displacing and your need to call your vet urgently.

Your vet will take follow-up X-rays that he can compare to the earlier X-rays to see what changes have happened. If you can stop the coffin bone from displacing the foot usually stabilizes. Once this happens you can start reversing the damage.

Long term hoof care

The laminae will not firmly reattach until a new, healthy hoof grows back, this can take as long as a year. Your horse will need corrective shoeing to support the hoof for that length of time. If there has been a rotation of the coffin bone getting them back to full work might not happen.

Involve your vet and farrier to plan your horse’s recovery. The goal is to encourage the hoof to grow out with the coffin bone aligned as closely to normal as possible.

Your vet can do updated X-rays to follow the coffin bone’s progress and your farrier can trim your horse’s toe and raise the heels of its hooves and fit corrective shoes. Regular follow-up visits will enable your horse’s progress to be carefully monitored and treated.

Management after Laminitis

If all goes well in the following months the normal wall of your horse’s hoof will grow down from the coronary band. During this time keep a watchful eye on your horse and his hooves to make sure his symptoms come back again.

Nutrition

There are many supplements and herbal products that aid hoof growth. Horses with metabolic problems need to be fed a low grain, high fiber diet and very good quality hay.

exercise

Doing too much exercise too soon is a risk. When your horse has passed the critical stage and moving comfortably you can hand walk him or put him in a small, soft-footed paddock. Deciding on when to let your horse out will depend on how badly affected his feet were, the more extreme the rotation of the coffin bone the longer your horse will need to be box rested.

Overweight horses can benefit from being out to lose weight and burn off calories.

Returning to full work will take time and will totally depend on the severity of the hoof changes. With slight changes, your horse can get back to work in a few months but in extreme cases, you might have to wait for the whole hoof to grow out.

Recovery from laminitis takes work and commitment from you, your vet, and your farrier. Careful treatment of the symptoms can get your horse back to full work after a bad case of laminitis.

in conclusion

Treating the initial infection whatever it may be as soon as possible gives your horse the best chance of recovering from this frightening illness. Once your horse has been confirmed to have laminitis careful treatment of your horse can help him heal safely and get him back to competition. This does not need to be a devastating prognosis.

Links for further reading

Laminitis – RVC Equine – Royal Veterinary College Laminitis is a common, extremely painful and frequently recurrent condition in horses, ponies and donkeys. It has significant welfare implications for owners.

Laminitis: Prevention & Treatment |Laminitis results from the disruption (constant, intermittent or short-term) of blood flow to the sensitive and insensitive laminae. These laminae structures …

Laminitis in Horses – Musculoskeletal SystemEquine laminitis is a crippling disease in which there is a failure of attachment of the epidermal laminae connected to the hoof wall from the dermal laminae …

One Comment